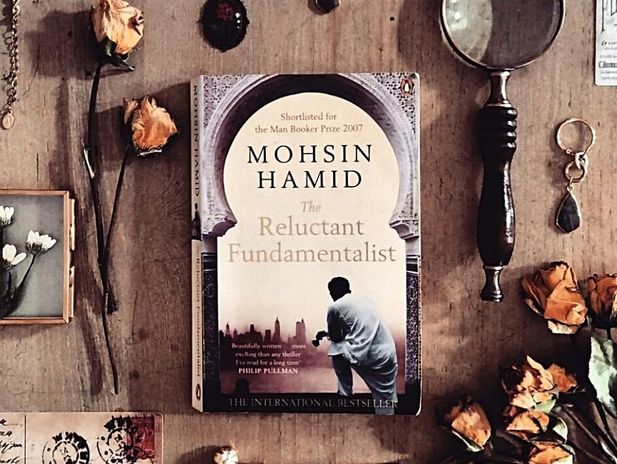

The Reluctant Fundamentalist

a novel by mohsin hamid

The 2007 novel by Mohsin Hamid, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is the story of an Ivy League bound pakistani immigrant, Changez, as his world is turned upside-down post-9/11 not only due to possibility of war a little too close to home, but the looming confusion of his own identity, is he an American or a Pakistani?

Though I find The Reluctant Fundamentalist a thorough 3.5 star read, I admit to being a little misled by the name. For me, the reluctant fundamentalist is a person with somewhat liberal values who reluctantly agrees to comply with the extremely radical principles of our fundamentalist society because that is part or stereotype of her national identity. A person who reluctantly but determinedly tries to pursue her culture despite prevailing traditional sometimes harmful norms.

I was maybe a bit too disappointed.

Initially, with the above idea in mind, I intended to see if the transition is even possible. To go with a more liberal and fulfilling perception of the world, to a more literal and religious one. I wanted to see, and prove that a person who would go through this tormentous process must feel similar to how I feel, furious and frustrated.

And though early signs in the novel, like in Changez’s pursuit to americanize himself but also remain hold of his past in Lahore, promised the above ending. But soon enough, the novel turned a round about to somewhere I did not see coming.

The plot

Changez, as he sits down with an American guest in his home city of Lahore, reminisces on the four years he spent in the United States.

As a Princeton alumni, he looks back with admiration on his campus which meant, for him, life had just begun and it showed no near signs of ending.

Here if he followed the lead of his established and esteemed professors and his likely smart fellows he could be anyone, anywhere, and make anything possible.

As a Princeton alumni, he looks back with admiration on his campus which meant, for him, life had just begun and it showed no near signs of ending. Here if he followed the lead of his established and esteemed professors and his smart likely fellows, he could be anyone, anywhere, and make anything possible.

‘This is a dream come true. Princeton inspired in me the feeling that my life was a film in which I was the star and everything was possible. I have access to this beautiful campus, I thought, to professors who are titans in their fields and fellow students who are philosopher-kings on the making.’

But with knowledge of the magnificence that he was a part of also came troubled embarrassment towards the un-magnificence of where he actually comes from, Pakistan.

Such comparisons trouble me too about how we now compare America and other developed countries with our own country and its lack of basic provenance. In fact, if you read about the Indus Valley civilisations about four thousand years ago, you’ll see how they had cities laid out on grids, and boasted underground sewers, while the ancestors of those who invaded and colonised America were illiterate barbarians.

Their present is magnificent as was our past.

‘Now our cities are largely unplanned, unsanitary affairs, and America had universities with individual endowments greater than our national budget for education. To be reminded of this vast disparity was, for me, to be ashamed.’

So naturally Changez did what any immigrant from a third-world country might do, cloak his identity.

‘I was the only non-American in our group, but I suspected my Pakistaniness was invisible, cloaked by my suit, by my expense account, and -most of all- by my companions.’

As Changez steps foot into one of the most prestigious quantifying firm in Wall Street- Underwood Samson, he not only leaves a lasting first impression - mostly due to his Lahori heritage - but also ranks top in his training at the company.

Underwood Samson’s primary focus was to precisely determine their client’s asset’s value. Focus on the fundamentals was their guiding principle, drilled into their trainees from the first day mandating a single minded approach to financial detail. It negated and taught the trainees to ignore their passionate pangs for the soon-to-be redundant workers by requiring a degree of commitment that left one with rather limited time for such distractions.

But his American Dream doesn’t end here. He is in fact reacquainted with his former princeton fellow, Erica, in New York after an earlier intimate bond made during a vacation in Greece. Erica due to a past trauma is mentally unsettled and is mostly disconnected from real life. As the novel progresses, Erica’s looming black shadow consumes her head and she falls back into depression and shuts herself down.

Erica is one of the central plots of this book and also one of the central criticisms I have of it. Mental illness is serious. People suffering from it need medical attention, but the way Pakistani authors (typically male) use the mental situation to paint pictures of heroines who are beautiful and brilliant but also utterly disillusioned and feeble is just grossly disgusting.

In my opinion, it makes them feel good about adoring women with equally good social and educational status who, in comparison to them, are still of inferior quality due to an imbalance of the mind and fallout of the emotional system. It creates the illusion of them being liberal and modern but also satisfies their egos knowing they are significantly superior to their women who need their ‘protection’ due to their ‘mental fragility’.

Anyway, Changez’s real journey of finding his identity truly starts after watching the headlines made after 9 September 2001.

He finds himself feeling considerate and worried about what was about to happen but also found himself smiling at the notion that America with all of her pride and superiority had been brought to her knees.

After that, its a rat’s chase where people in turbans, asians, bearded muslim men and muslim women in hijab, and pakistani blue-collar workers, all were almost beaten to death. With the FBI raiding mosques, shops, and people’s houses and the disappearance of many muslims into shadowy detention centers for questioning, Changez reasoned that most of them were exaggerated or untrue. He curbed his own doubts about his safety with the fact that such disasters befell on the hapless poor not Princeton graduates working in prestigious firms.

Over the course of the war on terror, Pakistan and India get each other’s noses and theres the possibility of war which especially heightened tensions since both countries contained nuclear capabilities.

When Changez returns home for the holidays, he felt his shame deepen when he first saw with his American eyes his shabby looking house with ceiling cracks, dry bubbles of paint, load shedding, and outdated furniture all representing inferiority.

It was when he regained his sense of self that he saw the building again, he realised that his provenance, his home, did not speak of lowliness but of enduring grandeur, of rich history.

‘It was far from impoverished; indeed, it was rich with history. I wondered how I could ever have been so ungenerous, so blind, to have thought otherwise, and I was disturbed by what this implied about myself: that I was a man lacking in substance and hence easily influenced by even a short sojourn in the company of others.’

During his stay in Lahore, he observed how even though the looming possibility of war and Wagah Border’s vulnerability, the probabilty of all the runways being nuked by the much bigger and stronger opponent, and most of all, the fear of being wiped from the face of humanity yet still the residents of Lahore did not stray from their everyday routines. For they woke up, went to schools, or their jobs, had brunches with friends, dinners with family and were tucked in bed by night.

On his flight to New York, Changez couldn’t help but feel guilty, and treacherous, like fleeing the battlefield while your friends and family are still fighting.

See when your country doesn’t feel worth saving, when your values, your principles, your people and your home isn’t valued and signified, isn’t instilled in one since birth with an undying love for nation, the biggest achievement in that place is to leave it.

’So many passengers were similar to me in age: college students and young professionals, heading back after the holidays. I found it ironic; children and the elderly were meant to be sent away from impending battles, but in our case it was the fittest and brightest who were leaving, those who in the past would have been most expected to remain.’

Then as time passes by a business trip brings him to Valparaíso, Chile, where he is told the story of the janissaries:

‘Then he asked, “Have you heard of the janissaries? ” “No”, I replied. “They were christian boys,” he explained, “captured by the ottomans and trained to be soldiers in a Muslim army, at that time the greatest army in the world. They were ferocious and utterly loyal: they had fought to erase their own civilisations, so they had nothing else to turn to.”’

I’d be lying if I said that it didn’t hit me hard. Apparently it had the same effect on Changez who - already struggling to maintain that single minded focus to his job - left Underwood Samson. With an expired visa, joblessness, and no reason to stay in the US, he leaves for Lahore.

But before he does, he tries to reconnect with Erica. You might be wondering what her end was. Well, prior to the trip to Chile, it came to be known that Erica was in a rehab facility, to come back from the depths of her thoughts without the shame one feels to see one’s fellows, friends, families, and coworker’s life moving on while theirs is stuck in one place, the only change being time.

However, when Changez visits the facility prior to his leaving for Pakistan, he learns that Erica had run away from the facility and was a missing person. Her clothes were found by the lake at the end of the forest near the facility with so sign of her body.

Changez realised that his lack of a stable core, of not knowing where he belonged - New York or Lahore - on both or in neither, was the reason when Erica asked for his ‘help’ he had nothing of substance to give her. His own identity was so fragile that he was incapable of offering her an alternative to the chronic nostalgia inside her, he was afraid that he might have helped push her in her own confusion.

It is in conversation to his guest, Changez expresses his disapproval of the way America operates in other’s business - in Korea, Taiwan, Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Vietnam.

‘I knew from my experiance as a Pakistani- of alternating periods of American aid and sanctions- that finance was a primary means by which the American Empire exercised it’s power.’

Upon returning to Pakistan, Changez, in his deepest grief on Erica’s disappearance, and very likey death, enters into the same frame of mind as Erica had. Although he is now a university professor in the finance department and is the forefronters to organise protest against American interference in state business, he lives his life with Erica as his wife (in his mind of course).

His students have been arrested in conspiracies involving terrorisms, he has been summoned to court multiple times in order to testify for their innocence or their possible conviction, and he is paranoid of being watched all the time.

The story is told in a provocative manner, the main construct being metafictional since we are brought back to present day with Changez conversing with his unsure American guest who is suspicious of everyone, from the dhabba waiter to the passing commonor, even at certain points from Changez himself. I believe the effect created was the address the issue of the fact that common Pakistani’s are seen as walking talking terrorists.

‘It seems an obvious thing to say, but you should not imagine that we Pakistanis are all potential terrorists, just as we should not imagine that you Americans are all undercover assassins.’

The conversation is muted at the other end, so the guest’s feelings, body language, words and actions are spoken for by Changez himself which gets a little awkward especially when the women from the National Arts Academy were being gazed at disturbingly by not only the guest but men in the surroundings, which was of course picked up by Changez. I feel like the mere insistence of the two men to keep calling them girls was reflective enough. Changez’s unending monologue during these conversations felt exhilarating and annoying, since he was also narrating every miniscule move in their backgrounds like the waiter fetching them coke, or dictating their menus.

I felt like the novel didn’t have much going on in the plot other than tense international relations between the United States, Native Americans towards coloured or mixed Americans, Pakistan and India. The rest was either Changez’s reaction towards them and his feelings of anxiety for his country and Erica. And although on a literary basis, the novel might be considered a good literary pierce involving precise state of mind of several Pakistanis even now (and I say that because I too resonated with a lot of stuff),it’s theme of historical fiction, and the author’s personal political opinions. I feel like if the sole purpose for picking it up is escapism or enjoyance, I wouldn’t highly recommend it.

But if you’re interested in a toxic love story or 'tragedy' involving a pakistani immigrant and a mentally off-balance americana, I’m sure you’d be satisfied.